The odds are not in your favour if you’re hoping to cruise through life, avoiding the crushing weight of mental illness. At the very least, someone you love has probably spent too many days feeling stripped of their identity.

Maybe that someone is you?

A staggering one-in-five Australians find themselves trapped inside the belly of the beast and cannot see a way out. Tragically, many go on to take their lives, with suicide being the biggest killer of young people across the nation.

For a scourge that’s so widespread, there’s so much we don’t know, or are not willing to talk about.

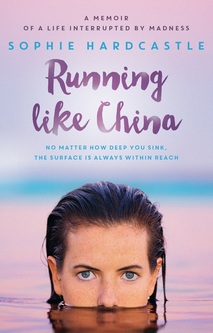

Just ask Sophie Hardcastle, author of Running like China, a brave memoir about her battle with bipolar and her stubbornness to thrive, in spite of it. “We don’t have enough education, even in schools when I was growing up…not knowing is what scares people the most,” she tells me, as we meet to discuss her book.

Maybe that someone is you?

A staggering one-in-five Australians find themselves trapped inside the belly of the beast and cannot see a way out. Tragically, many go on to take their lives, with suicide being the biggest killer of young people across the nation.

For a scourge that’s so widespread, there’s so much we don’t know, or are not willing to talk about.

Just ask Sophie Hardcastle, author of Running like China, a brave memoir about her battle with bipolar and her stubbornness to thrive, in spite of it. “We don’t have enough education, even in schools when I was growing up…not knowing is what scares people the most,” she tells me, as we meet to discuss her book.

The twenty-one year old shares so much of herself, hoping to help others by breaking down the stigma that allows mental illness to fester in the shadows. This is Sophie’s first book, and she’s genuinely surprised that I’ve read it all. It was impossible not to, the enchanting way she writes feels like an intimate conversation, making it the perfect delivery for her challenging life.

As a young girl, Sophie was in love with the world, rising at dawn to surf in the ocean before heading to school. She was full of energy, with an infectious laugh and a competitive streak that saw her attracting sponsors and thriving in surfing events.

Her mantra was to live life to the fullest, and she did, until she became a stranger in her body at the age of seventeen, when she was drained of energy and haunted by hallucinations that gave way to a pattern of self-harm.

Sophie says she didn’t realise what was happening until she was submerged in darkness and couldn’t see a way out. She turned to drugs, alcohol and sex in a desperate attempt to feel something, and when that no longer worked, she tried to take her life.

Family and friends rallied behind her as she was admitted to hospital and eventually diagnosed with bipolar.

Sophie remembers the awkwardness that crept into the room with well-meaning visitors, who didn’t know how to react. After all, what do you say to someone who’s circling the depths of despair? It’s tempting to tiptoe around, out of fear that anything more than polite conversation could be triggering.

A few friends decided to throw caution to the wind anyway, by taking on a mission to make Sophie laugh. She writes about the hilarious lengths they went to, reminding her that she is alive. Humour was her saving grace, and one tool that makes difficult themes in this book easy to digest.

“If there was ever an elephant in the room when they visited, their humour would have taken a black marker from my pencil case and drawn a thick black moustache above the elephant’s trunk, and we would have laughed at the absurdity.” Sophie in Running like China

But not everyone has been understanding. A friend once told Sophie he thought she could overcome depression if she really wanted to. This was a kick in the guts, trivialising her illness and adding to self-doubt.

“I also find it so ironic, people telling me that it’s all in my head, because it is, it’s a chemical imbalance in my head and it shouldn’t be taken any less seriously than someone having a stone in their kidney or a tumour,” she says.

No stranger to hospitals, Sophie was taking a cocktail of drugs that were prescribed to silence her mind, but also took a toll on her body. She completely changed the way she eats, following the advice of a naturopath, which helped her body to handle the medication. This boosted her recovery, along with extensive therapy and the practise of mindfulness.

As a young girl, Sophie was in love with the world, rising at dawn to surf in the ocean before heading to school. She was full of energy, with an infectious laugh and a competitive streak that saw her attracting sponsors and thriving in surfing events.

Her mantra was to live life to the fullest, and she did, until she became a stranger in her body at the age of seventeen, when she was drained of energy and haunted by hallucinations that gave way to a pattern of self-harm.

Sophie says she didn’t realise what was happening until she was submerged in darkness and couldn’t see a way out. She turned to drugs, alcohol and sex in a desperate attempt to feel something, and when that no longer worked, she tried to take her life.

Family and friends rallied behind her as she was admitted to hospital and eventually diagnosed with bipolar.

Sophie remembers the awkwardness that crept into the room with well-meaning visitors, who didn’t know how to react. After all, what do you say to someone who’s circling the depths of despair? It’s tempting to tiptoe around, out of fear that anything more than polite conversation could be triggering.

A few friends decided to throw caution to the wind anyway, by taking on a mission to make Sophie laugh. She writes about the hilarious lengths they went to, reminding her that she is alive. Humour was her saving grace, and one tool that makes difficult themes in this book easy to digest.

“If there was ever an elephant in the room when they visited, their humour would have taken a black marker from my pencil case and drawn a thick black moustache above the elephant’s trunk, and we would have laughed at the absurdity.” Sophie in Running like China

But not everyone has been understanding. A friend once told Sophie he thought she could overcome depression if she really wanted to. This was a kick in the guts, trivialising her illness and adding to self-doubt.

“I also find it so ironic, people telling me that it’s all in my head, because it is, it’s a chemical imbalance in my head and it shouldn’t be taken any less seriously than someone having a stone in their kidney or a tumour,” she says.

No stranger to hospitals, Sophie was taking a cocktail of drugs that were prescribed to silence her mind, but also took a toll on her body. She completely changed the way she eats, following the advice of a naturopath, which helped her body to handle the medication. This boosted her recovery, along with extensive therapy and the practise of mindfulness.

Her strong connection to nature also saved her mind. This is obvious in her writing style, which draws upon the ocean as a powerful metaphor to explain her struggle. Sophie says the rawness of the earth is grounding, reminding her of who she is. She also channels a certain magic into her writing, by using descriptors such as “the man with the snow beard” to identify people, a choice she says was born out of an appreciation for qualities that make people unique.

Although Sophie has come a long way, she still has bipolar. China is her nickname, and previously she’s hidden behind that identity to reject the part of her that has a mental illness. This was liberating at first, but ultimately made relapsing more difficult to cope with. She’s learnt that acceptance is vital, and now has strategies in place to soften the blow when the “dormant volcano” erupts.

Sophie’s sharing these lessons by speaking at schools, through her involvement with Batyr, an organisation encouraging young people to talk about mental illness. She says it’s crucial for people to be honest about how they feel, and for supporters to listen, even if they don’t know what to say.

She’s grateful she waited out the storm, for the moments that now cause her to catch her breath in awe. Most of all, Sophie wants to stress that survival is about patience. Navigating mental illness is like riding out a tricky wave when surfing: “If I am held beneath and tossed like a rag doll, I know to remain calm, and to savour the air in my lungs because inevitably I will float to the surface.”

I originally interviewed Sophie for The Wire current affairs, community radio program.

Although Sophie has come a long way, she still has bipolar. China is her nickname, and previously she’s hidden behind that identity to reject the part of her that has a mental illness. This was liberating at first, but ultimately made relapsing more difficult to cope with. She’s learnt that acceptance is vital, and now has strategies in place to soften the blow when the “dormant volcano” erupts.

Sophie’s sharing these lessons by speaking at schools, through her involvement with Batyr, an organisation encouraging young people to talk about mental illness. She says it’s crucial for people to be honest about how they feel, and for supporters to listen, even if they don’t know what to say.

She’s grateful she waited out the storm, for the moments that now cause her to catch her breath in awe. Most of all, Sophie wants to stress that survival is about patience. Navigating mental illness is like riding out a tricky wave when surfing: “If I am held beneath and tossed like a rag doll, I know to remain calm, and to savour the air in my lungs because inevitably I will float to the surface.”

I originally interviewed Sophie for The Wire current affairs, community radio program.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed